I’m often asked to explain what an Open Hybrid Cloud is to those interested in cloud computing. Those interested in cloud computing usually includes everyone. For these situations, some high level slides on the what cloud computing is, why it’s important to build an Open Hybrid Cloud, and what the requirements of an Open Hybrid Cloud are usually enough to satisfy.

In contrast to everyone interested in cloud, there are system administrators, developers, and engineers (my background) who want to understand the finer details of how multi-tenancy, orchestration, and cloud brokering are being performed. Given my background, these some of my favorite conversations to have. As an example, many of the articles I’ve written on this blog drill down to this level of discussion.

Lately, however, I’ve observed that some individuals – who fall somewhere in between the geeks and everyone else – have a hard time understanding what is next for their IT architectures. To be clear, having an understanding of the finer points of resource control and software defined networking are really important in order to ensure you are making the right technology decisions, but it’s equally important to understand the next steps that you can take to arrive at the architecture of the future (an Open Hybrid Cloud).

With that in mind let’s explore how an Open Hybrid Cloud architecture can allow organization to evolve to greater flexibility, standardization, and automation on their choice of providers at their own pace. Keep in mind, you may see this same basic architecture proposed by other vendors, but do not be fooled – there are fundamental differences in the way problems are solved in a true Open Hybrid Cloud. You can test whether or not a cloud is truly an Open Hybrid Cloud by comparing and contrasting it against the tenants of an Open Hybrid Cloud as defined by Red Hat. I hope to share more on those differences later – let’s get started on the architecture first.

Side note – this is not meant as the only evolutionary path organizations can take on their way to an Open Hybrid Cloud architecture. There are many paths to Open Hybrid Cloud! 🙂

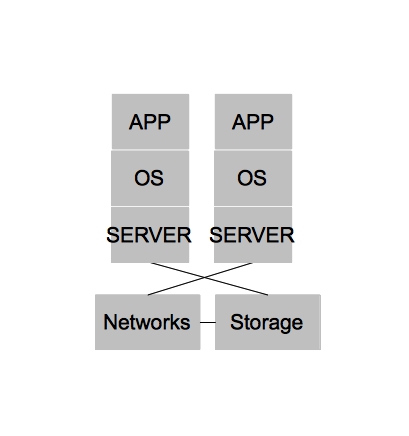

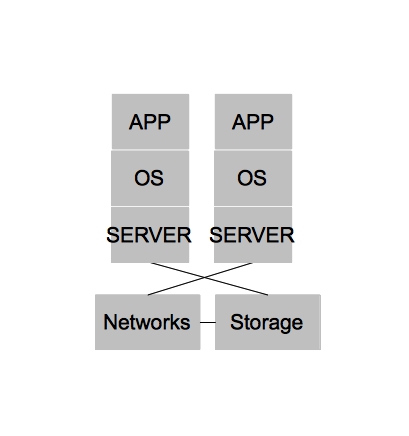

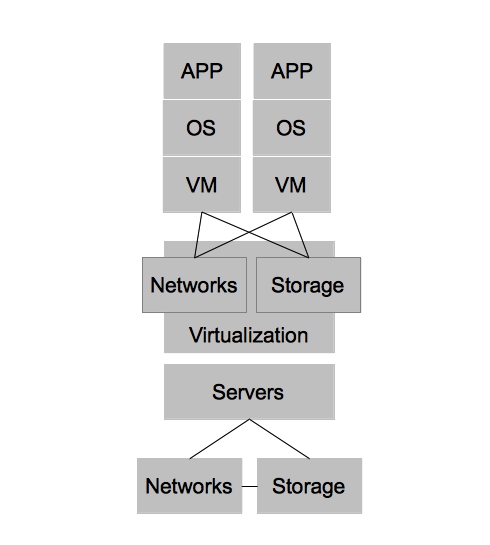

In the beginning [of x86] there were purely physical architectures. These architectures were often rigid, slow to change, and under utilized. The slowness and rigidity wasn’t necessarily because physical hardware is difficult to re-purpose quickly or because you can’t achieve close to the same level of automation with physical hardware as you could with virtual machines. In fact, I’m fairly certain many public cloud providers today could argue they have no need for a hypervisor at all for their PaaS offerings. Rather, purely physical architectures were slow to change and rigid because operational processes were often neglected and the multiple hardware platforms that quickly accumulated within a single organization lacked well defined points of integration for which IT organizations could automate. The under utilization of physical architectures could be largely attributed to operating systems [on x86], which could not sufficiently serve multiple applications within a single operating system (we won’t name names, but we know who you are).

Side note – for the purposes of keeping our diagram simple, we will group the physical systems in with the virtualized systems. Also, we won’t add all the complexity that was likely added due to changing demands on IT. For example, an acquisition of company X – two teams being merged together, etc. You can assume wherever you see architecture there are multiple types, different versions, and different administrators at each level.

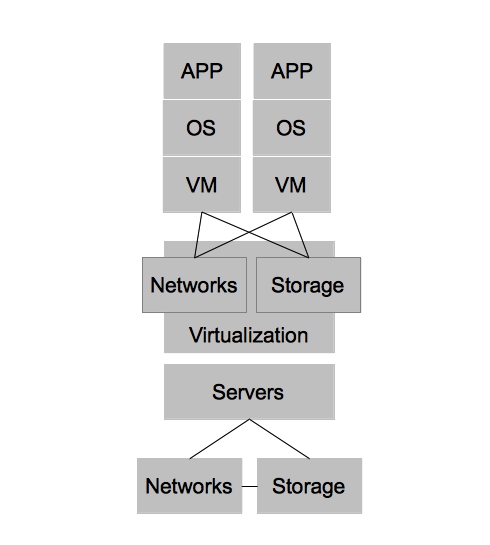

Virtualized architectures provided a solution to the problems faced in physical architectures. Two areas in which virtualized architectures provided benefits are by allowing for higher utilization of physical hardware resources and greater availability for workloads. Virtualized Architectures did this by decoupling workloads from the physical resources that they were utilizing. Virtualized architectures also provided a single clean interface by which operations could request new virtual resources. It became apparent that this interface could be utilized to provide other users outside IT operations with self-service capabilities. While this new self-service capability was possible, virtualized architectures did NOT account for automation and other aspects of operational efficiency, key ingredients in providing end users with on demand access to the compute resources while still maintaining some semblance of control required by IT operations.

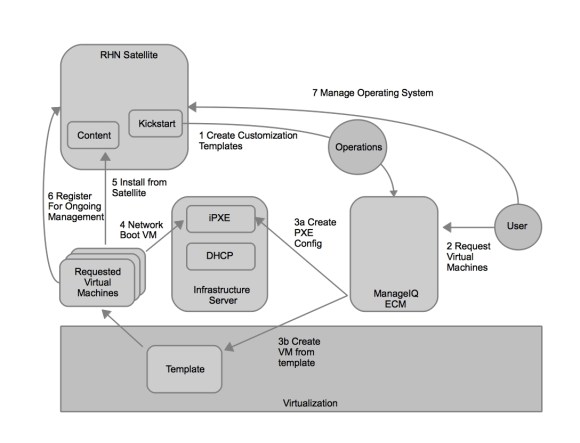

In order to combine the benefits of operational efficiency with the ability for end users to utilize self-service, IT organizations adopted technologies that could provide these benefits. In this case, I refer to them as Enterprise Cloud Management tools, but each vendor has their own name for them. These tools provide IT organizations the ability to provide IT as a Service to their end customers. It also provided greater strategic flexibility for IT operations in that it could decouple the self-service aspects from the underlying infrastructure. Enforcing this concept allows IT operations to ensure they can change the underlying infrastructure without impacting the end user experience. Enterprise Cloud Management coupled with virtualization also provides greater operational efficiency, automating many of the routine tasks, ensuring compliance, and dealing with the VM sprawl that often occurs when the barrier to operating environments is reduced to end users.

Datacenter virtualization has many benefits and coupled with Enterprise Cloud Management it begins to define how IT organization can deliver services to its customers with greater efficiency and flexibility. The next generation of developers, however, have begun to recognize that applications could be architected in such ways that are less constrained by physical hardware requirements as well. In the past, developers might develop applications using a relational database that required certain characteristics of hardware (or virtual hardware) to achieve a level of scale. Within new development architectures, such as noSQL for example, applications are built to scale horizontally and are designed to be stateless from the ground up. This change in development impacts greatly the requirements that developers have from IT operations. Applications developed in this new methodology are built with the assumption that the underlying operating system can be destroyed at any time and the applications must continue to function.

For these types of applications, datacenter virtualization is overkill. This realization has led to the emergence of private cloud architectures, which leverage commodity hardware to provide [largely] stateless environments for applications. Private cloud architectures provide the same benefits as virtualized datacenter architectures at a lower cost and with the promise of re-usable services within the private cloud. With Enterprise Cloud Management firmly in place, it is much easier for IT organizations to move workloads to the architecture which best suits them at the best price. In the future, it is likely that lines between datacenter virtualization and private clouds become less distinct– eventually leading to a single architecture that can account for the benefits of both.

As was previously mentioned, Enterprise Cloud Management allows IT organizations to deploy workloads to the architecture which best suits them. With that in mind, one of the lowest cost options for hosting “cloud applications” is in a public IaaS provider. This allows businesses to choose from a number of public cloud providers based on their needs. It also allows them to have capacity on demand without investing heavily in their own infrastructure should they have variable demand for workloads.

Finally, IT organizations would like to continue to increase operational efficiency while simultaneously increasing the ability for its end customers to achieve their requirements without needing manual intervention from IT operations. While the “cloud applications” hosted on a private cloud remove some of the operational complexity of application development, and ultimately deployment/management, they don’t address many of the steps required to provide a running application development environment beyond the operating system. Tasks such as configuring application servers for best performance, scaling based on demand, and managing the application namespaces are still manual tasks. In order to provide further automation and squeeze even higher rates of utilization within each operating system, IT organizations can adopt a Platform as a Service (PaaS). By adopting a PaaS architecture, organizations can achieve many of the same benefits that virtualization provided for the operating system at the application layer.

This was just scratching the surface of how customers are evolving from the traditional datacenter to the Open Hybrid Cloud architecture of the future. What does Red Hat provide to enable these architectures? Not surprisingly, Red Hat has community and enterprise products for each one of these architectures. The diagram below demonstrates the enterprise products that Red Hat offers to enable these architectures.

Area Community Enterprise

Physical Architectures Fedora Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Datacenter Virtualization oVirt Red Hat Enterprise Virtualziation

Hybrid Cloud Management Aeolus/Katello CloudForms/ManageIQ EVM

Private Cloud OpenStack Stay Tuned

Public Cloud Red Hat’s Certified Cloud Provider Program

Platform as a Service OpenShift Origin OpenShift Enterprise

Software based storage Gluster Red Hat Storage

Areas of Caution

While I don’t have the time to explore every differentiating aspect of a truly Open Hybrid Cloud in this post, I would like to focus on two trends that IT organizations should be wary of as they design their next generation architectures.

The first trend to be wary of is developers utilizing services that are only available in the public cloud (often a single public cloud) to develop new business functionality. This limits flexibility of deployment and increases lock-in to a particular provider. It’s ironic, because many of the same developers moved from developing applications that required specific hardware requirements to horizontally scaling and stateless architectures. You would think developers should know better. In my experience it’s not a developers concern how they deliver business value and at what cost of strategic flexibility they deliver this functionality. The cost of strategic flexibility is something that deeply concerns IT operations. It’s important to highlight that any applications developed within a public cloud that leverages that public clouds services are exclusive to that public cloud only. This may be OK with organizations, as long they believe that the public cloud they choose will forever be the leader and they never want to re-use their applications in other areas of their IT architecture.

This is why it is imperative to provide the same level of self-service via Enterprise Cloud Management as the public cloud providers do in their native tools. It’s also important to begin developing portable services that mirror the functionality of a single public provider but are portable across multiple architectures – including private clouds and any public cloud provider that can provide Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). A good example of this is the ability to use Gluster (Red Hat Storage) to provide a consistent storage experience between both on and off premise storage architectures as opposed to using a service that is only available in the public cloud.

The second trend to be wary of is datacenter virtualization vendors advocating for hybrid cloud solutions that offer limited portability due to their interest in preserving the nature of proprietary hardware or software platforms within the datacenter. A good example of this trend would be a single vendor advocating replication of a single type of storage frame be performed to a single public cloud providers storage solution. This approach screams lock-in beyond that of using just the public cloud and should be avoided for the same reasons.

Instead, IT organizations should seek to solve problems such as this through the use of portable services. These services allow for greater choice of public cloud providers while also allowing for greater choice of hardware AND software providers within the virtualized datacenter architecture.

I hope you found this information useful and I hope you visit again!